Sex, Power, Oppression: Why Women Wear High Heels

Our relationship with heels is a long and complicated source of feminist debate. Despite it all, as Summer Brennan writes, women still love them

‘Heels made me feel powerful in a womanly way.’ Photo Credit : Christian Vierig | Getty Images

There was a time in my life in New York City when I wore high heels almost every day. I myself did not have much power, but I worked at the United Nations, in a place where powerful people congregate. It is a place of suits and ties, skirts and silk blouses; of long speeches and aggressive air conditioning; of Your Excellency, and Madam Chairperson, and freshly shined wingtips and yes, high heels.

There was an image in my mind of a certain kind of woman professional, feminine, poised that I wanted to embody. I saw these women daily, year after year, backstage to the halls of power, on benches by the ladies’ room, changing in and out of comfortable and uncomfortable shoes.

These were power heels, and they were worn by women from all over the world. They were leopard print, or green and scaly. They were amaranthine and violaceous and subtly velvet. They were black and shiny as Japanese lacquer, with a shock of red on the sole. Some were plain, but uncomfortable anyway. Perhaps I have embellished them somewhat in my imagination, my memory tempered by glamour. What is not in dispute is that all of these statement shoes invariably came with a steel-spined appendage like an exclamation point: stiletto, the heel named for a dagger. For the women whose feet put up a fight, these shoes were changed out of and put away, smuggled in and out of the building in handbags, like weapons.

When I worked in a formal office setting, high heels were never of any special interest to me beyond the fact that I liked them, and wore them, and liked wearing them. I didn’t fixate. I never owned too many. If I’m honest, there were times when I liked the idea of wearing them more than the actual wearing of the shoes. Still, without high heels, at work I didn’t feel quite put together. Like a man might feel who has forgotten to put on his necktie in a boardroom full of men in neckties. They made me feel powerful in a womanly way; suited up, compliant, like I was buckled in to the workday.

Perhaps I had something to prove; or perhaps I had been made, repeatedly, to think that.

For better or worse, the high heel is now womankind’s most public footwear. It is a shoe for events, display, performance, authority and urbanity. In some settings and on some occasions, usually the most formal, it is even required. High heels are something like neckties for women, in that it can be harder to look both formal and femme without them. Women have been compelled by their employers to wear high-heeled shoes in order to attend work and work-related functions across the career spectrum, from waitresses in Las Vegas to accountants at PricewaterhouseCoopers.

It’s a shoe for when we’re on, for ambition; for magazine covers, red carpets, award shows, boardrooms, courtrooms, parliament buildings and debate lecterns. Rather paradoxically or maybe not according to the 150-year-old fetish industry, it has also consistently been viewed as a shoe for sex.

For women, what is the most public is also the most private, and vice versa. Along with being our most public shoe, it is also considered the most feminine.

And so, again and again I have found that the question of high heels to wear them or not to wear them, what they mean or don’t mean, signify or don’t signify, ask for or don’t ask for has been an unlikely but fertile locus of feminist debate.

Modern elevated shoes were born in Paris, invented and then reinvented for western fashion as the classic high heels we recognize today. The first came in the 17th century at the court of King Louis XIV, when blocky talons hauts, inspired by Middle Eastern riding shoes, were deemed the best way for a nobleman to accentuate the muscles of his silk-stocking-clad calves and proclaim his status.

The second came in the 1950s when Dior designer Roger Vivier put steel rods into the shafts of skinny stilettos, raised their height to three inches or more, and encouraged regular women to wear them in daily life. Thus, in the postwar era, when an emergency female workforce had recently been shuffled back to the kitchen, the template for the contemporary high heel made its debut.

Vivier, a Frenchman, had been making custom high heels for the likes of Josephine Baker and Queen Elizabeth II since the 1930s. He was among the first mainstream designers to push his creations to the edges of practicality and into the realm of art. He was not the first to use steel in his heels, nor were his shoes the first to feature heels that were both very high and very thin. But it was his work with Dior in the 1950s that finally made the look de rigueur.

A woman at train station changing shoes. Photo Credit : H Armstrong Roberts | Retrofile | Getty Images

A woman at train station changing shoes. Photo Credit : H Armstrong Roberts | Retrofile | Getty Images

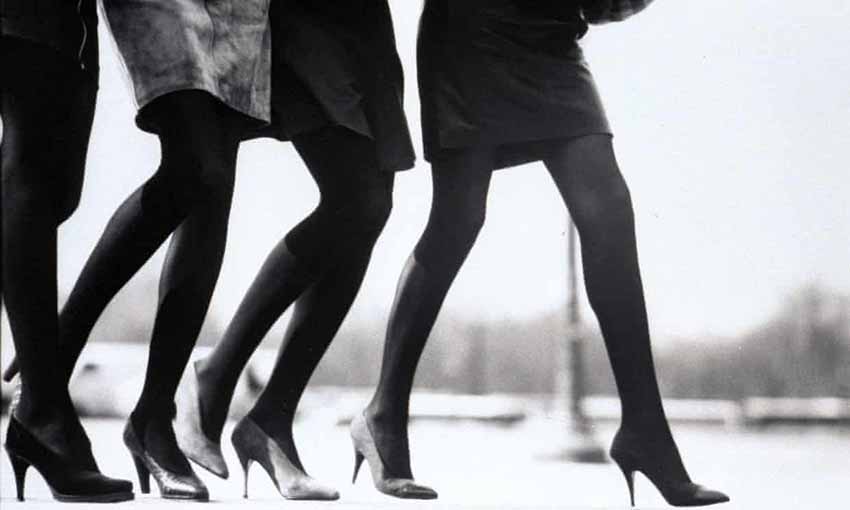

Four models in a 1987 Vogue photoshoot. Photo Credit : Arthur Elgort | Conde Nast | Contour Style by Getty Images

Four models in a 1987 Vogue photoshoot. Photo Credit : Arthur Elgort | Conde Nast | Contour Style by Getty ImagesFrom the creations of Vivier, to Manolo Blahnik, Jimmy Choo, Christian Louboutin, and Alexander McQueen, so many modern high heel designs embody ideas of metamorphosis. The fashion gods transform women into something other than human. They become plant-like, animal-like; elevated, but also easier to catch and subdue.

When asked what men find attractive about a woman in high heels, the French shoe designer Christian Louboutin, speaking to fashion photographer Garance Doré in his Parisian apartment in 2013, replied that it was the fact that the heels slowed the woman down, giving the man more time to look at her. Louboutin said nothing about aesthetics, only speed. “What is the point of wanting to run?” he said, “I am all for the pace getting slower, and high heels are very good for that.”

A woman in motion, outside of male control, has long been viewed as a problem. What better way to tame these fleeing women than to literally root them to the soil?

But look. I still want to wear dresses and high heels. I like my femininity, or what I have been acculturated to think of as “my femininity”, even if it is cultural. I do not want to have to imitate a man, in behavior or in appearance, in order to have power and freedom. If I want to run, I’ll put on running shoes. I like to wear makeup. I enjoy adornment.

Maybe you do, too, regardless of your gender. In Bad Feminist, writer Roxane Gay defends such stereotypical “female” things as her love of pink, rejecting the idea that feminism must exclude the trappings of female culture. Can we claim power as women without also denigrating girliness? Can’t even cultural femininity be rescued from patriarchy and its metaphors of oppression?

We are in a decades-long process of finding out what a free woman can look and act like, which will probably take centuries more to determine. We’re still sorting out the relationship between glass ceilings and glass slippers. For now, the idea of doing something “in high heels” is a near-universally understood shorthand meaning both that the person doing it is female, and that in doing it, she faces additional, gendered challenges.

High heel sandals with a long satin bow with fruit motifs by Christian Louboutin. Photo Credit : Christian Vierig | Getty Images

High heel sandals with a long satin bow with fruit motifs by Christian Louboutin. Photo Credit : Christian Vierig | Getty ImagesOne must be careful not to hold up the metaphor for the thing above the thing itself. Constrictive clothing and high heels might have prevented many Victorian women from climbing mountains, literal or figurative (although some did it anyway), but their problem was not one of fashion.

What confines, impoverishes, exploits, enslaves, oppresses, sickens, bloodies, rapes and kills women are not generally clothes or shoes, but rather laws and societal norms. Prejudice. Misogyny. White supremacy. Transphobia. Homophobia. Predatory corporations and unfair labor laws. Discriminatory work and hiring policies. Lack of legal protection from violence in the workplace, home and street. Non-enforcement of existing protections. Weaponized bureaucracy. Overpriced women-specific services. Medical sexism. Religious sexism. Barred access to property ownership, financial management, a credit card or a checkbook. Threat of violence in public spaces, both physical and virtual, and on public transportation systems. The mobility of women is and has been restricted physically through fashion, but most of all it has been restricted legally, financially, professionally, medically, intellectually, sexually, politically. That is to say, systemically.

The dominant narratives in society and media still struggle to see women as individuals. We are more often flavors, types. Public feminist intellectuals are routinely castigated for criticizing individual women with whom they disagree, even when that disagreement has not been expressed in a gendered or sexist manner. It comes up a lot when women fight about whether or not they should wear high heels.

When women are not seen fully as people, we are all the same, and criticizing one of us means criticizing all of us.

This article originally appeared on : The Guardian

-

Indigenous people march in Brazil to demand land demarcation

2024-04-24 -

Talks on global plastic treaty begin in Canada

2024-04-24 -

Colombian court recognizes environmental refugees

2024-04-24 -

Asia hit hardest by climate and weather disasters last year, says UN

2024-04-23 -

Denmark launches its biggest offshore wind farm tender

2024-04-22 -

Nobel laureate urges Iranians to protest 'war against women'

2024-04-22 -

'Human-induced' climate change behind deadly Sahel heatwave: study

2024-04-21 -

Moldovan youth is more than ready to join the EU

2024-04-18 -

UN says solutions exist to rapidly ease debt burden of poor nations

2024-04-18 -

Climate impacts set to cut 2050 global GDP by nearly a fifth

2024-04-18