'Our Futures Are At Stake': Sport's Climate Crisis Weakness And How To Change It

Athletes don’t want to be accused of hypocrisy but the changing environment is already having an impact on many sports

Clockwise from top left: the Arsenal squad pose for a picture on the steps of their plane; tennis fans stand in a line next to water fans during the Australian Open; Will Gadd ice climbing near the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro; sprinklers are turned on following an ICC U19 Cricket World Cup match. Composite: Getty Images, EPA, Red Bull

For a sector of society so adept at harnessing communities, cities, even entire countries, sport is strangely weak at empowering action on the issue which matters most. Perhaps the pace of sport, the relentless rotation of preparing, travelling and performing, restrains us from stopping, breathing and thinking about the existence of sport as we know it.

Having globe-hopped for 25 years, reporting on Olympics, Paralympics, World Cups and tennis grand slams, I know I’ve taken sport for granted. When it stops – rain delay, postponement, pandemic – we notice. At other times, it’s just there. Silly games, essentially, for escapism and entertainment.

Striking is how rarely we consider the impact of the climate crisis on something we love to play and watch. We need to pause.

That tennis match we watched; have we considered the impact of the surface and surroundings on the real heat and impact on the human body? Forty degrees in the air, perhaps, but radiant temperature more likely into the 60s. If those numbers keep rising, for how long is it sustainable?

That cricket match we enjoyed; how much water was required to maintain the pitch? Are we aware how even a small temperature increase affects evaporation of fresh water, impacts on topsoil and implications for farmers growing our food?

These, I must confess, often appear questions to park away for another day. But making the new documentary series Emergency on Planet Sport has opened my eyes to the scale and urgency of the challenge. As Steve Isaac, the sustainability director of the R&A, says: “My main concern is the lack of recognition of golf clubs and sports clubs in general about what’s coming our way. Unless you’re aware of that, how can you prepare?”

We need to present this conversation in more stark terms. Some links golf courses, for example, face an existential threat not in the future, but now. Before lockdown I visited Montrose, on the east coast of Scotland, to witness first-hand the voracious North Sea eating alive the fifth oldest course in the world. Only a small portion remains of the old 3rd tee, the rest is on the beach in morbid clumps of turf. A path, connecting tee with fairway, simply disappears off the cliff face. They’re losing two metres of coastline a year. The scale of erosion really shook me.

.jpg)

Impacts of the climate crisis, in particular, increase in extreme weather patterns, rising seas and temperatures, resonate throughout the series. Will Gadd, the ice climber who scaled Kilimanjaro in 2014 and 2020, recalls: “Everything was half the size it used to be or just gone. Imagine if you walked downtown to your office and your whole office was gone, in fact the whole of downtown was gone. I’ve got to find a different way to do my sport.”

The former Australian rugby union international David Pocock wants more engagement: “As athletes, we all have a role to play because the climate crisis is a challenge we have to face. Our futures are at stake and I think there’s some sort of moral obligation for everyone to be playing their role. We need to up our ambition.”

Among athletes, I’ve discovered an understandable fear of hypocrisy. Sport is global and we all fly, whether to participate, watch or, yes, report. But, as Pocock says, reassuringly: “The idea that because you drive a car or fly means you have no right to talk about action on climate change doesn’t sit well with me. Athletes speaking out really does lead to important conversations among young people and who knows where that can lead.”

The Southampton midfielder Oriol Romeu admits he’s no expert but has a willingness to learn: “We are the ones living on this planet. We have to react before we’re too late. I hope we don’t regret afterwards, saying: ’We should have done this or should have done that.’ I’d rather do it now.”

The 2015 French Open runner-up Lucie Safarova has concerns for the future of tennis in some parts of the world if warming continues. Heatstroke can end a career; just listen to Amy Steel, a former Australian international netballer who collapsed after a match in 2016, never to play again, even struggling to get out of bed some days. Remembering her match with Li Na in Melbourne in 2014, Safarova says: “I looked up during a changeover to see burnt leaves falling on to the court from outside, and at that moment I thought: ‘This is insane, are we really playing tennis in this weather?’”

Many governing bodies are examining renewable energy, food provision and recycling efforts. But this should be standard and things need to move quicker. The GB Olympic rowing hopeful Melissa Wilson believes we can learn from Covid‑19 adaptability: “Even last year the conversations I was having on the rowing team were more along the lines of: ‘Can we have a compost bin in the team room.’ Now it feels like the scale of the conversation that can happen is so much greater.”

Look at Formula One. A two-year plan to end on-site TV production at every race, shipping tonnes of freight every week, happened for eight weeks because of the pandemic. A London base, rather than a flying circus, has significantly reduced their carbon footprint and they won’t stop there. F1 innovation, vital in the fight against Covid, intends to work for the climate fightback too.

Making this series has been a journey of discovery for me. I love sport and I love the planet – probably, I admit, in that order. I’ll be switching those priorities. As one of the commissioned pieces of performance poetry which start each episode says: “Before the TVs and the phones can display it, what use is sport with no world on to play it?”

-

Climate impacts set to cut 2050 global GDP by nearly a fifth

2024-04-18 -

US sterilizations spiked after national right to abortion overturned: study

2024-04-13 -

Future of Africa's flamingos threatened by rising lakes: study

2024-04-13 -

Corporate climate pledge weakened by carbon offsets move

2024-04-11 -

Humanity lost 'moral compass' on Gaza: top UN official

2024-04-10 -

No.1 Scheffler says patience and trust are secrets to success

2024-04-10 -

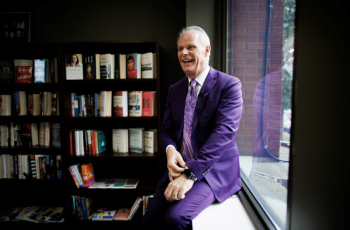

From homeless addict to city chief: the unusual journey of Canadian mayor

2024-04-10 -

Slovenian spiderwoman Garnbret eyes more Olympic climbing gold

2024-04-07 -

Academic freedom declining globally, index finds

2024-04-04 -

Zimbabwe declares El Nino drought a national disaster

2024-04-03