COVID-19 Update: Johnson & Johnson Plans To Test Vaccine On Children Soon

J&J's COVID-19 vaccine uses a cold virus to deliver coronavirus genetic material to spur an immune response with the help of a platform - called AdVac, also used in the Ebola vaccine

It is important for drugmakers to test their vaccines on children, said US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

US-based pharmaceutical and consumer packaged goods developer Johnson & Johnson (J&J) is planning to start testing its experimental COVID-19 vaccine in youths aged 12 to 18 soon. Dr Jerry Sadoff of J&J, during a virtual meeting of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, said, "We plan to go into children as soon as we possibly can, but very carefully in terms of safety."

Rival drugmaker Pfizer Inc has already begun testing its COVID-19 vaccine with Germany's BioNTech on children as young as 12. Their vaccine uses mRNA, a new technology that is yet to produce an approved vaccine.

J&J started testing the vaccine in adults in a 60,000-volunteer Phase III study in late September but had to pause the trial earlier this month because of an adverse medical event in one participant. The testing resumed last week.

The company, depending on safety and other factors, also plan to test the vaccine on younger children, said Sadoff.

J&J stated that the company's previous experience with the same vaccine technology used successfully in children could give it an upper hand with regulators. Currently, J&J is in discussions with regulators and partners regarding the inclusion of the pediatric population in its trials.

It is important for drugmakers to test their vaccines on children, said US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, some doctors have raised concerns that in some children the vaccines themselves could trigger a rare and life-threatening condition called Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome.

J&J's COVID-19 vaccine uses a cold virus to deliver coronavirus genetic material to spur an immune response with the help of a platform - called AdVac, also used in the Ebola vaccine.

Dr Paul Spearman, Director of the infectious diseases division, Cincinnati Children's Hospital said the technology's history of safety should be important to regulators.

He added, "Most of the toxicities are going to come from the platform and not from putting a different insert into the platform," Spearman said. So, replacing the Ebola genetic material with that of the novel coronavirus "is unlikely to give you major issues."

-

Moldovan youth is more than ready to join the EU

2024-04-18 -

UN says solutions exist to rapidly ease debt burden of poor nations

2024-04-18 -

'Human-induced' climate change behind deadly Sahel heatwave: study

2024-04-18 -

Climate impacts set to cut 2050 global GDP by nearly a fifth

2024-04-18 -

US sterilizations spiked after national right to abortion overturned: study

2024-04-13 -

Future of Africa's flamingos threatened by rising lakes: study

2024-04-13 -

Corporate climate pledge weakened by carbon offsets move

2024-04-11 -

Humanity lost 'moral compass' on Gaza: top UN official

2024-04-10 -

No.1 Scheffler says patience and trust are secrets to success

2024-04-10 -

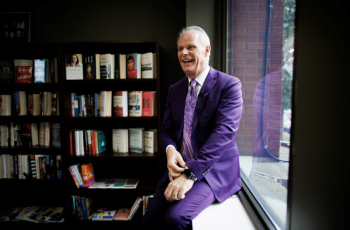

From homeless addict to city chief: the unusual journey of Canadian mayor

2024-04-10