Smartphones Transformed Everything. Now, There’s More Disruption To Come.

Smartphones upended every element of society during the last decade, from dating to dinner parties, travel to politics. This is just the beginning.

Illustrations from the last decade of our smartphone coverage, by (from left) Jon Krause (“Step Away From the Phone,” 2018) and Rami Niemi (“The New Rules for Checking a Smartphone at Dinner,” 2014). ILLUSTRATION: FROM LEFT: JOHN KRAUSE; RAMI NIEMI

THE ADVENT of the smartphone marked the merging of man and machine. These devices might not be embedded into our forearms just yet, but they have so seismically changed how we operate and interact as humans over the past decade that we’re all effectively cyborgs now. We’re each wholly devoted to these tiny unknowable machines, rarely out of hand or at the very least rarely out of reach.

IBM’s ill-fated Simon Personal Communicator—released in 1994 and best known for its appearance in the equally ill-fated 1995 Sandra Bullock film “The Net”—was the first touch-screen machine to merge phone, email and PDA. It took 2007’s first-gen iPhone, however, to spark the smartphone’s rise from novelty to ubiquity. In early 2010, hand-held devices took a major leap, with global sales doubling from roughly 50 million devices in the first quarter of that year to about 100 million in the fourth quarter, just as “Off Duty” was first documenting sweater trends. Smartphone-sales-per-quarter eventually surged to a peak of more than 400 million units during the final few months of 2016.

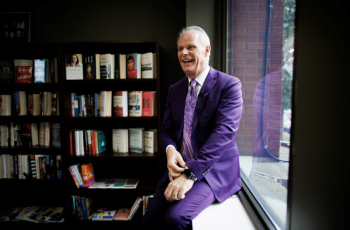

As our digital addiction grew, so did our dependence on apps, said Shawn DuBravac, futurist and the bestselling author of “Digital Destiny: How the New Age of Data Will Transform the Way We Work, Live, and Communicate.” The ease that each little temptress of an icon offered, whether to call an Uber, order Seamless or find a mate, created the “disruption” that defined the 2010s. “All the good that smartphones have brought—and all the bad they’ve brought—over the last 10 years is because smartphones made transactions easier,” said Mr. DuBravac.

Now in 2020, the smartphone runs a close second to oxygen as an essential. For many, it’s the lone way we communicate and share. It can quickly call up any ounce of information discovered in human history, letting us answer “Why Your Labradoodle Is Shivering” via YouTube and end bar-stool debates about interchangeable “Rocky” sequels or whether procrastination is really one of the Seven Deadly Sins. It lets us produce art, document revolutions and let our voices be heard at any instance from anywhere. It can help us find love, seek validation—or pick at insecurity like a scab—through an endless hunt for “Likes.”

It has engulfed our wallets and stereos, cameras and GPS systems, newspapers and gaming machines. Apps let it transform into a book, a TV remote or a carpenters’ level. I mostly use mine to look at pictures of other people’s dogs on Instagram.

Off Duty covered the smartphone since the beginning, when in the first issue editor Kevin Sintumuang asked “What Kind of E-Reader Are You?” But we quickly discovered that the smartphone was no mere piece of tech, and breathlessly and often optimistically detailed its incursions into fashion and food, design and travel. To wit: pieces like 2018’s “Thank U, Text” about e-commerce shopping, and our 2015 feature “Found in Translation” that weighed the pros and cons of apps that instantaneously decode foreign menus in far-flung locales.

Ironically, however, the smartphone also effectively snuffed out the concept of being “off duty.” Laptops made the workplace mobile, but smartphones tethered us to the office in a way we never thought possible—something I was struggling with in 2018 until my iPhone gave out, plunging me first into panic and then a kind of calm. This led to our 2018 piece on “Always On” culture titled “Far From the Maddening Co-Workers.” We continued to seek distance from our devices, going as far earlier this year to argue for a cheeky paper version of a phone developed by Google.

Almost inconceivably, Mr. DuBravac thinks the strengths of 5G and cellular connectivity “will make us more reliant on the smartphones because they’ll interact with more things throughout our worlds,” adding to the ways these devices become extensions of our bodies. When the next phase of the Cyborg Revolution starts, you can read about it here.

This article originally appeared on : The Wall Street Journal

-

Moldovan youth is more than ready to join the EU

2024-04-18 -

UN says solutions exist to rapidly ease debt burden of poor nations

2024-04-18 -

'Human-induced' climate change behind deadly Sahel heatwave: study

2024-04-18 -

Climate impacts set to cut 2050 global GDP by nearly a fifth

2024-04-18 -

US sterilizations spiked after national right to abortion overturned: study

2024-04-13 -

Future of Africa's flamingos threatened by rising lakes: study

2024-04-13 -

Corporate climate pledge weakened by carbon offsets move

2024-04-11 -

Humanity lost 'moral compass' on Gaza: top UN official

2024-04-10 -

No.1 Scheffler says patience and trust are secrets to success

2024-04-10 -

From homeless addict to city chief: the unusual journey of Canadian mayor

2024-04-10