Why I’m Training to Help People Face-up to Death

We all need to be better at talking about death, it's one of the few certain things we all have in common

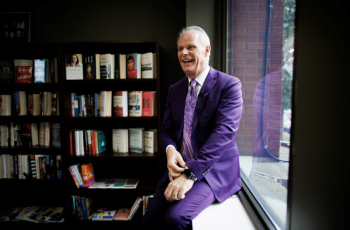

Photo Credit : BBC

In many ways, I’m just like any other 25-year-old. I love clubbing especially when the music is good decent house music and techno. Floating Points is probably my favourite DJ, all that feel-good soul music, he’s the man. But, I also want to help people prepare for death.

My official title is death doula. If doctors are there to look after our medical needs when we die, then doulas help to support the dying and their families emotionally at the end of lives.

I guess that’s not something you often hear from someone my age. I appreciate that for many, being so interested in issues surrounding death is considered weird, but for me, it’s a passion. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly where it comes from, but, I think it's mainly because of my relationship with my younger brother, Owen.

Owen had cerebral palsy, a condition which left him confined to a wheelchair and unable to speak. Being so close to someone whose life was of such a significantly different quality to mine, shaped my perspective growing up. It made me think about the quality of a person’s life rather than the length of it.

Owen’s needs were great. He required almost 24/7 care, and because he was the youngest of five, it was a real challenge for my mum and dad to balance everything. As I got older, I began to help out more. My mum did everything she could for Owen, often sleeping next to him to help him breathe at night.

The bond Owen and I shared was really special. Although Owen couldn’t speak, he had a wonderfully expressive face and a massive personality trapped in his restricted body. He had one of the most vibrant smiles I’ve ever seen. He didn’t really need to speak, it would have been easier of course but his personality always shone through and everyone has such wonderful memories of him.

Owen died two years ago, aged 20. And while we knew his death was inevitable, it still came as a surprise to us. As a family, it’s not like we were living under the shadow of his imminent death. But, because we had an understanding that he was likely to die young, we made sure he had the opportunity to live his life to the full.

In 2015, roughly a year before he died, Owen was taken into hospital with serious breathing difficulties and we feared the worst. He stayed in for a month and eventually had a tracheostomy inserted a tube which bypasses a blockage to make sure a person can get enough air.

He did come home but things were different. We were grateful this gave us another year with him, but I can’t pretend his quality of life didn’t deteriorate. It was heartbreaking to see. During this time, my family and I had to come to terms with everything. It was kind of an acceptance that’s the best way to describe it.

Around this time, I began a masters in medical ethics and law. I moved home, back in with my parents to save money. It meant I was fortunate enough to spend Owen’s last few months with him. My memories of that time are very dear to me. Not only because of the jokes we shared together, but because it was an opportunity to begin to grieve with him, rather than without him.

Sadly, it seems we don’t think about saying goodbye until it’s too late.

One night in 2016, my mum and I were discussing the best course of action for Owen if he stopped breathing during the night. Would it be right to attempt CPR or put him through more invasive treatments to keep him alive? Would that really be best for him? I understand this is uncomfortable for some people to get their head around because we have a culture of denying death, pretending it doesn’t exist and prolonging life at any cost. But Owen helped me to understand the importance of talking about these things openly.

As it turned out, that was our last opportunity to speak hypothetically about Owen’s death: he ended up passing away at about 5am in his bed.

A hundred years ago, it was usual for people to die at home. These days, most people die in hospitals even though 70% say they’d rather die at home. Having Owen die peacefully at home made me want to help other people experience that too. We got to spend final, precious time with him in our house, and it helped with my grieving. It was also the catalyst for me looking into end of life care work.

I realised I wanted to do something to physically help people. It couldn’t be abstract like working as a lawyer who might help with a contract for example. It needed to be more hands-on. This was when I found out about the doula role.

There are about 150 death doulas across Britain working in hospitals, hospices and in people’s homes and the number is continuing to grow. I wasn’t aware they existed before Owen’s death, or that this was actually a job I could do, but I was instantly drawn to it. I signed up for the doula training course and, fittingly, it began around the first anniversary of Owen’s death. I think I found it or it found me at the perfect time in my life. There are three elements to the course and I began the final part of the training in June.

A doula is not a doctor we don’t provide medical care. Instead, we provide emotional support. We listen and do our best to make sure a dying person’s wishes are carried out. We also learn how to take care of the body after death at home so it doesn’t have to be taken away immediately. This is an important part of the process it avoids too much intrusion at what can be a difficult time, and gives loved ones a chance to say goodbye on their own terms.

Even though I’m almost a qualified doula, life since Owen’s death has still been incredibly difficult. I felt as if I had lost a piece of me the only person I could truly be myself around was gone, and I can’t begin to imagine the pain my parents must have felt. But I worked really hard at trying to understand what I was feeling.

Owen’s death left me feeling resilient, and inspired by his courage. He’d been through so much and still came out of it with a smile. His life and death was, and still is, my motivation to help others. I think we all need to be better at talking about death it’s one of the few certain things we all have in common and not talking about it only reinforces fear.

Thinking so much about dying and being around death has definitely changed my perspective. The stuff we worry about day to day money, our careers, how we look how much does it really matter? I’m only young, and I’m sure I’ll face challenges in the future but, for now, this is the way I’m trying to live my life.

Ultimately, I believe we shouldn’t let fear of death fear of anything, really get in the way of living life.

This article originally appeared on : BBC

-

Moldovan youth is more than ready to join the EU

2024-04-18 -

UN says solutions exist to rapidly ease debt burden of poor nations

2024-04-18 -

'Human-induced' climate change behind deadly Sahel heatwave: study

2024-04-18 -

Climate impacts set to cut 2050 global GDP by nearly a fifth

2024-04-18 -

US sterilizations spiked after national right to abortion overturned: study

2024-04-13 -

Future of Africa's flamingos threatened by rising lakes: study

2024-04-13 -

Corporate climate pledge weakened by carbon offsets move

2024-04-11 -

Humanity lost 'moral compass' on Gaza: top UN official

2024-04-10 -

No.1 Scheffler says patience and trust are secrets to success

2024-04-10 -

From homeless addict to city chief: the unusual journey of Canadian mayor

2024-04-10